Viewpoint: India must not expand its drug protection programme – here’s why

Avi Chaudhuri, 28-Oct-2025

India has just floated a proposal to greatly expand its QR coding programme for protection against counterfeit medicines. That same platform however was earlier compromised with fake QR codes appearing on counterfeit drugs in mere months after rollout. This article is an excerpt of my letter to the Indian Health Ministry arguing why further expansion of its deeply flawed programme will lead to the certainty of catastrophic outcomes across all sectors of Indian society.

The QR coding programme announced by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in late 2022 to protect the top 300 medicines in India against counterfeiting was based on a deeply flawed design. The result has been that consumers were not given the protection envisioned and instead the platform provided counterfeiters with a golden opportunity to capitalize on those very QR codes to further propagate their malicious acts against the nation.

Here, I provide a detailed analysis of the serious problems affecting the current QR coding platform and the public harm it will create if it stays in place, and far worse, if it is expanded. My arguments for abandoning the proposed expansion is divided into five sections, with key points supported by evidence from the public domain.

1) QR codes suffer from serious security flaws

QR codes come in two versions — open and closed. The latter form requires a dedicated reader or mobile application and is considered to be more secure [1]. A notable example where a closed barcode is used is UNICEF’s Traceability and Verification System (TRVST) that has been rolled out in a few countries to protect vaccines [2]. If a 2D barcode is to be used, then it must be deployed in conjunction with its own dedicated application to create a secure authentication platform.

The Indian QR coding programme is unfortunately based on an open format where an inserted link provides the gateway for verification. Open QRs are really used only for marketing purposes that guide a consumer to a brand owner’s website or product portal. These became highly common during the COVID pandemic, such as on restaurant menus and other engagement materials.

The Health Ministry’s choice of using open QR codes in the current drug protection programme was therefore most surprising because of their extreme vulnerability to multiple attack vectors [3-6]. Major federal agencies in the United States, such as the FBI and FTC, had already issued public warnings on the danger of QR codes [7-9]. Various experts had also weighed in with their views on the dangers of using QR codes [10-12]. Taken together, there existed irrefutable evidence that QR codes should never have been adopted in the first place because they are just not fit for use as a security tool.

There are no product security programmes anywhere, much less one to stop counterfeit drugs, that are based on open QR codes.

2) India’s current programme has already suffered major problems

The above concerns are not just theoretical but borne out by India’s unfolding experience that started in mere months after rollout. It has now emerged that the very QR code meant to protect Indian consumers has itself been compromised through copied versions appearing on fake medicines [13,14]. Although it is expected that counterfeiters will use every means to defeat a new product security system, the vulnerability of open QR codes however allowed several medicines to be easily compromised to then appear in the market shortly after programme launch.

Fake QR codes have now been found on fake medicines across India for treatment of high blood pressure [15], diabetes [16], blood clotting [17], vertigo [18] and epilepsy [19]. Four of these products belonged to drug makers that opted to follow a QR coding format designed by European standards organization GS1, thereby highlighting the fact that even a much-hyped platform rolled out with great fanfare by an esteemed global agency is no match for the guile of Indian counterfeiters [20].

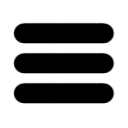

The case with Sun Pharma’s epilepsy drug Levipil is a notorious example of cybercrime where a sophisticated operation allowed large numbers of genuine serial numbers to be procured by criminal entities, which were then placed into QR codes on fake versions of the drug [21]. The origin of the digital leakage was either the code generating source (Delhi-based IT company PharmaSecure) or the code application site (Sun Pharma plant in Assam). Repeated calls for these companies to disclose the source of the digital theft have gone unanswered and Sun Pharma has thus far refused to recall the product even with the possibility that fake Levipil batches still remain in the market [22].

Given India’s experience, we can imagine the certain catastrophe that would unfold through further programme expansion into life-saving drugs. Vaccines would certainly be a prime target, as evidenced by recent cases of fake COVID [23] and rabies vaccines [24]. Similarly, fake versions of oncology drugs have also plagued India, such as the cases involving Roche products Herceptin, Neulastim and others. I was involved in wiping out that problem from India a decade back by way of a unique non-clonable security label. Although our effort led to the elimination of fake cancer drugs in India within a few months, the criminals behind that operation quickly found alternate markets including the USA [25] and others where the problem persists to this day [26,27].

The proposed expansion of the QR coding scheme to now include vaccines, antibiotics and oncology drugs will mean that these life-saving medicines will be just as easily targeted with fake codes, bringing certain calamity to Indian consumers.

3) Consumers face the illusion of false reassurance

As discussed above, perfect replicas of a genuine QR code can arise either through outright duplication from an authentic drug package in the market or by way of data theft to create many digital twins. One unfortunate aspect of the current programme is that drug companies are not given any guidance on what actions to take when their QR programme has been compromised. Levipil is an excellent exemplar because the problems with it have now been well studied [28].

As can be seen in the figure, both genuine and fake Levipil packs return exactly the same message after a QR scan, i.e., key drug details as required under the regulation (see screenshots at figure bottom). Those details continue to be pushed out by Sun Pharma on fake versions even today as this article went to press many months after the problem was discovered. This troubling fact can be confirmed by scanning the QR code from a verified fake package (see red-bordered inset on right). That should not happen under any circumstances because it gives the strong impression that the fake drug is authentic by virtue of all expected product details being sent to the phone.

The more alarming aspect of this case, however, is that scanning the QR code on a fake package returned the declarative statement “This is a Genuine Pack”, just as with the genuine product (see screenshots and accompanying blue-bordered insets for clarity). This is of course a false message and it has been infuriating to understand why Sun Pharma and PharmaSecure continue to provide such an overt confirmation of authenticity on a fake product more than six months after the counterfeiting attack took place and when they are both fully cognizant of the exact batch numbers that were compromised.

Put simply, there is nothing worse than for a patient to believe that a genuine medicine is being consumed when in fact it is a fake product. The continued projection of a counterfeit drug being authentic with full foreknowledge of the facts represents a stunning level of incompetence (or indifference) by the drug maker. A scan of any Levipil package from the known compromised batches should immediately bring up a red flashing alert to avoid that medicine, and nothing else. This failure of corporate accountability is enabled by the absence of regulatory protection from the Health Ministry, thus creating a permissive environment for a lackadaisical approach to consumer safety by Sun Pharma.

The illusion of authenticity from false reassurance to a patient after scanning a fake QR code represents a highly dangerous outcome, and one that will be far more devastating with life-saving medicines through the proposed expansion of the QR coding programme.

4) The current QR coding regulation suffers from serious other flaws

Although the choice of using open QR codes was a critical programmatic error, there were other parts of the regulation that also contributed to creating the current debacle [29]. This section will cover just two of those unfortunate decisions by the Health Ministry.

The current regulation makes no mention of requiring a unique serial number to be embedded in each QR code. Consequently, more than one-third of the drug makers avoided serializing the barcode entirely and opted to cut corners by using batch number coding instead [30]. The batch number, which encompasses thousands of medicine packs collectively from that production lot, is then used to retrieve and send the data associated with that product.

Counterfeiters can have a field day with drugs that follow this coding scheme because the probability of detecting a fake product then becomes negligible due to the many packages clubbed under it. It is fundamentally unknowable to the brand owner and health inspectors whether multiple successful authentications arose due to the same QR code appearing on many fake packs or whether many different customers were authenticating genuine packs from that same batch. The counterfeiter can even place a batch number-based QR code as part of the package artwork because there is no individual pack variability. And those drugs will always be positively authenticated all the while consumers are actually ingesting a fake medicine.

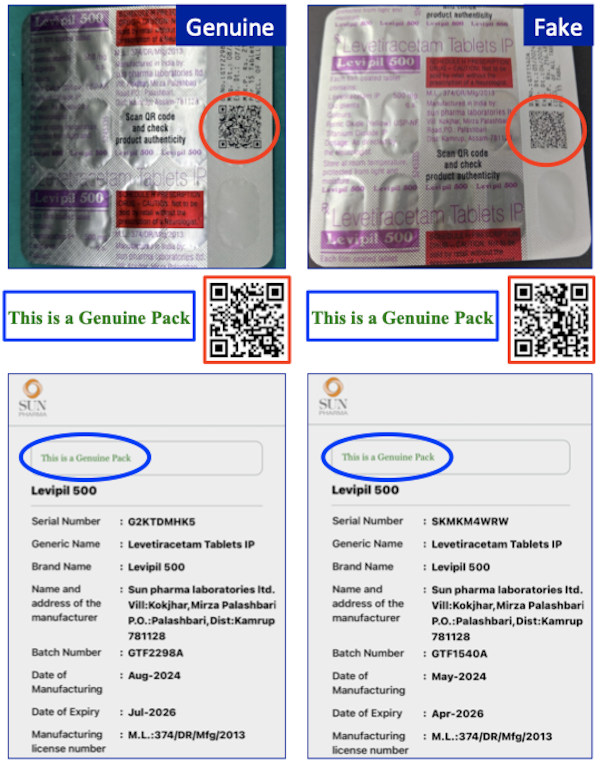

This peril is further aggravated by another flaw in the regulation, as described by way of the figure using the example of Augmentin Duo, the highest selling medicine in India. This antibiotic is distributed to pharmacies via a secondary polycarton (shown in the left panel), which in turn contains 10 blister strips.

The problem in this case arises because the QR code is missing from the consumer-facing product (i.e., the blister) and instead appears only on the secondary carton (circled in red and shown magnified in the inset). Thus, a mandated solution meant to reassure patients is missing from the very item they purchase. It is a certainty that few customers would seek to examine the secondary carton. And that in turns sets up an ideal scenario where counterfeiters can distribute fake blister strips of this product to retail pharmacies with the full knowledge that even genuine blisters lack any means for consumer verification. The entire QR coding mandate becomes irrelevant when consumer drug packages are exempt from protection, which is a serious loophole in the current regulation.

This setup also creates substantial jeopardy to pharmacists that can best be understood by considering the following scenario. Let’s assume that to protect his business and customers, a pharmacist scans each arriving secondary (polycarton) code to be assured that it is a genuine pack, and by extension so are its contents. Now, what if those secondary packages were actually counterfeit versions with a fake QR code and fake drugs inside? The retailer in this case would receive an identical scan outcome as if the secondary packs were actually genuine, and even with a reassuring “Verified Product” declaration (right panel in the figure). Counterfeiters can thus use clandestine supply channels to propel their fake medicines in the market because they now have a government-authorized tool at their disposal to deceptively convince downstream traders that their products are actually authentic.

It impossible to catch counterfeit medicines through non-serialized batch number-based QR codes on secondary packages, a fact that will cause far greater harm if the current programme is expanded to life-saving medicines.

5) Key stakeholders will be harmed if the current platform is expanded

As discussed in the prior four sections, the serious flaws in the current regulation will be amplified manyfold if the platform is expanded to cover additional drug categories. In this section I provide an outline of the specific harm that will befall virtually every key stakeholder in the Indian pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Drug makers will be harmed due to high susceptibility that the QR codes being mandated upon their products can be so easily compromised. That jeopardy was contained till now because a relatively small group of products required compliance. The proposed expansion will cover a far greater range of medicines across the full economic strata of the industry where many companies will struggle to deploy an effective and compliant outcome. The likely shortcut will be to rely on batch-numbered codes on secondary packs, which in turn will escalate vulnerability of their products and patients. The current programme design is just not suited for such a large-scale national mandate.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) will be harmed due to the substantial cost of compliance. Whereas the current regulation largely targeted big drug makers [31], the proposed expansion will no longer be confined to the largest selling products but rather the entire set of drugs in the affected categories made by all manufacturers regardless of size. SMEs will face huge compliance costs that may not be sustainable, starting with capital expenses for industrial inkjet printers, vision systems for print verification and solution provider engagement followed by ongoing operating costs for ink cartridges, authentication delivery, cloud management, subscriptions, service and maintenance.

Whereas the large companies can spread that cost over a larger production volume, SMEs will be hard hit because those same setup and running costs would apply to their much smaller volumes thus escalating their per-item cost for compliance in a highly disproportionate and discriminatory manner.

Pharmacists and wholesalers will be harmed by the mere fact that they are the last link in the distribution chain and therefore will be subjected to substantial scrutiny any time a fake QR-laden medicine should pop up. Each unfolding incident will bring outrage from their customers for having sold that fake drug. The Augmentin illustration provides an excellent example of the peril they face. Those drug makers that pursue coding only on secondary polycartons will create a perfect storm of opportunity for misleading the retail community and further perpetuate fake versions of their products.

Another source of harm will come from small drug makers having to increasingly cut GMP corners to remain competitive. One way for SMEs to control costs will be to source discounted ingredients that will in turn make them susceptible to substandard compositions, as highlighted by the recent cough syrup tragedy in India [32]. A blanket mandate that affects all drug makers across the board will create far greater incidence of both counterfeit and substandard formulations for which pharmacists as the final handlers of those products will bear the brunt of societal accusation.

Doctors (and nurses) will be harmed when they will inevitably be implicated for administering a fake vaccine to a patient that in turn leads to an adverse outcome. A very realistic scenario arises when a doctor or nurse follows the reasonable act of drug authentication through the QR code. However, if that code turns out to be a fake version placed on a counterfeit vaccine, the caregiver will then become entwined in the ensuing harm (or perhaps death) that would unfold with near certainty. The psychological trauma they will face from patient and family accusations of wrongdoing will bring substantial personal and professional harm.

Patients will be harmed from the convergence of all the facts and factors discussed in the foregoing sections. But there is still one further scenario that will create an insurmountable interdiction challenge. Whereas counterfeiters have thus far relied on QR duplication and cybercrime, there exists an even more treacherous possibility.

The open nature of the QR codes in India’s current regulation invites criminals to insert codes with a link to an alternate site where all authentications are positively returned, even mimicking the exact feedback from a genuine version [33]. This operation, known in the security field as QR phishing (quishing), has not yet been reported in India though its presence may also have been undetected. A well-designed quishing operation would be extremely difficult to detect and will only turn up after harm is caused to a consumer because the fake drug failed to have its intended therapeutic effect.

Each and every key stakeholder across the full pharmaceutical ecosystem will face undeniable and likely unrecoverable harm from programme expansion. The only beneficiaries will be GS1 and its technology enablers, both reaping massive future revenue by delivering a flawed programme that will hurt all other sectors of Indian patient care.

6) Turning the page … and doing this right

The most troubling outcome of the current regulation is that counterfeiters could so quickly and easily capitalize on a nationally mandated programme, something that was entirely predictable and actually predicted as far back as 2018 [34]. The Levipil incident shows that even many months after discovery, fake versions continue to mislead patients after scanning its QR code. The certainty of catastrophic results will unfold if a similar outcome were to befall a large swath of life-saving medicines through programme expansion. Fake medicines will then be discovered only when they fail to produce the intended therapeutic effect or lead to a serious adverse outcome. QR codes on the fake drug packages will actually be inconsequential to the discovery.

A nation that must rely on the chance possibility of counterfeit detection from a medical failure has abdicated the right to claim success of its regulated solution. The sad reality is that a programme that was meant to protect the Indian people has now become a vehicle to empower counterfeiters so that they can proceed with even more brazen acts of fraud. In short, India’s programme is now a gift to the counterfeiters.

The Indian Health Ministry can however get this right by undertaking much needed revision to its current platform or replacing it with a programme that would be far more effective, enduring and economical. It is even possible to implement a solution that brings parity across the industry so that SMEs, which are the backbone of the Indian health care system, are not economically discriminated. I have published a framework for just such a plan to serve as a starting point for discussion and debate [35].

7. References

[1] https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/3844090/A%20Gift%20to%20Counterfeiters.pdf

[3] https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/guidance/security-considerations-qr-codes-itsap00141

[4] https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/blog-post/qr-codes-whats-real-risk

[5] https://www.kaspersky.com/resource-center/definitions/what-is-a-qr-code-how-to-scan

[6] https://cyber-center.org/qr-codes/

[7] https://www.ic3.gov/PSA/2022/PSA220118

[8] https://threatpost.com/fbi-malicious-qr-codes/177902/

[12] https://news.va.gov/136377/think-twice-before-you-scan-qr-codes/

[13] https://www.thedailyhints.com/west%20bengal-news/details/542

[14] https://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid=178145&sid=3

[18] https://drugscontrol.org/news-detail.php?newsid=42246

[20] https://www.expresspharma.in/a-defining-opportunity-for-clarity-from-gs1/

[21] https://www.expresspharma.in/a-troubling-new-development-in-indias-qr-code-saga/

[22] https://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid=179088&sid=1

[23] https://academic.oup.com/pmj/article/98/e2/e115/7019565#google_vignette

[25] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fake-cancer-drug-surfaces-again-from-overseas/

[27] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanonc/article/PIIS1470-2045(24)00293-6/abstract

[28] https://www.expresspharma.in/sun-pharma-must-immediately-declare-a-voluntary-recall-of-levipil-500/

[31] Ibid.

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025_India_cough_syrup_crisis

[33] https://sosafe-awareness.com/glossary/quishing/

Dr Avi Chaudhuri is an acclaimed expert in the field of anti-counterfeiting, working with both governments and the private sector. He founded The Kulinda Consortium, a global alliance of solution providers that focuses on emerging nations to protect their citizens from fake drugs.

Dr Chaudhuri is now engaged in designing anti-counterfeiting programmes for several countries across Africa, working closely with senior government officals. The Kulinda programme in Tanzania-Zanzibar rolled out in 2024 resulted in the complete elimination of counterfeit medicines within four months of launch for products on which his solution was applied.

Related articles:

- Is India thinking again about QR barcoding for drugs?

- Indian cough syrup death toll reaches 26

- India's QR code programme: Part 3 - how to repair and reform

- Nigeria looks at use of QR codes to deter counterfeiting

- GS1 – friend or foe to India's medicines coding system?

- Gujarat hit by wave of falsified QR codes on medicines

- India's QR code programme: Part 2 - rating the drug makers

- Unlicensed medicines factory shut down in India

- India's drug QR code programme: anatomy of a debacle

- Seizure points to frailties in India's anti-fake meds system

- USTR highlights fake pharma in Notorious Markets report

- CDSCO under fire from industry over substandard drug alert

- Indian pharmacy group seeks action on 'spurious' meds

- India unveils upgraded GDP standard to fight illegal meds

Click here to subscribe to our newsletter

28-Oct-2025

Related articles:

- Is India thinking again about QR barcoding for drugs?

- Indian cough syrup death toll reaches 26

- India's QR code programme: Part 3 - how to repair and reform

- Nigeria looks at use of QR codes to deter counterfeiting

- GS1 – friend or foe to India's medicines coding system?

- Gujarat hit by wave of falsified QR codes on medicines

- India's QR code programme: Part 2 - rating the drug makers

- Unlicensed medicines factory shut down in India

- India's drug QR code programme: anatomy of a debacle

- Seizure points to frailties in India's anti-fake meds system

- USTR highlights fake pharma in Notorious Markets report

- CDSCO under fire from industry over substandard drug alert

- Indian pharmacy group seeks action on 'spurious' meds

- India unveils upgraded GDP standard to fight illegal meds

Sponsored Content

The Dark Side of Imitation – Counterfeit Alcohol and the Fight for Safety

The Transported Asset Protection Association (TAPA) has published a white paper on the scourge of counterfeit alcohol in response to a string of high-profile incidents that have claimed hundreds of lives.

The document details some of the most notorious incidents in recent years and explains how a brand protection standard (BPS) developed by TAPA Asia Pacific (TAPA APAC) can strengthen the supply chain against counterfeit goods by encouraging logistics companies to "design out" vulnerabilities. Read more

Sponsored Content

The Dark Side of Imitation – Counterfeit Alcohol and the Fight for Safety

The Transported Asset Protection Association (TAPA) has published a white paper on the scourge of counterfeit alcohol in response to a string of high-profile incidents that have claimed hundreds of lives.

The document details some of the most notorious incidents in recent years and explains how a brand protection standard (BPS) developed by TAPA Asia Pacific (TAPA APAC) can strengthen the supply chain against counterfeit goods by encouraging logistics companies to "design out" vulnerabilities. Read more

Press Releases

-

》 Antares Vision Group and Spherity expand partnership with reseller agreement to deliver DSCSA ATP credentials

-

》 TraceLink customers demonstrate readiness as DSCSA dispenser deadline arrives

-

》 Manufacturo and SolarFlexes partner to modernize utility-scale solar hardware production and traceability

-

》 4th Forum Unique Codes – Securikett brings experts together to discuss the security of the Digital Product Passport

Partners